Shell Plant [1]

The U. S. Rubber Company, locally called the “Shell Plant,” was located 10 miles south of Charlotte on York Road in the Steele Creek area of Mecklenburg County. The land is now part of Charlotte and is located near the southeast corner of the intersection of Westinghouse Boulevard and South Tryon, also known as Highway 49. The purpose of the plant was to build ammunition for the war effort.

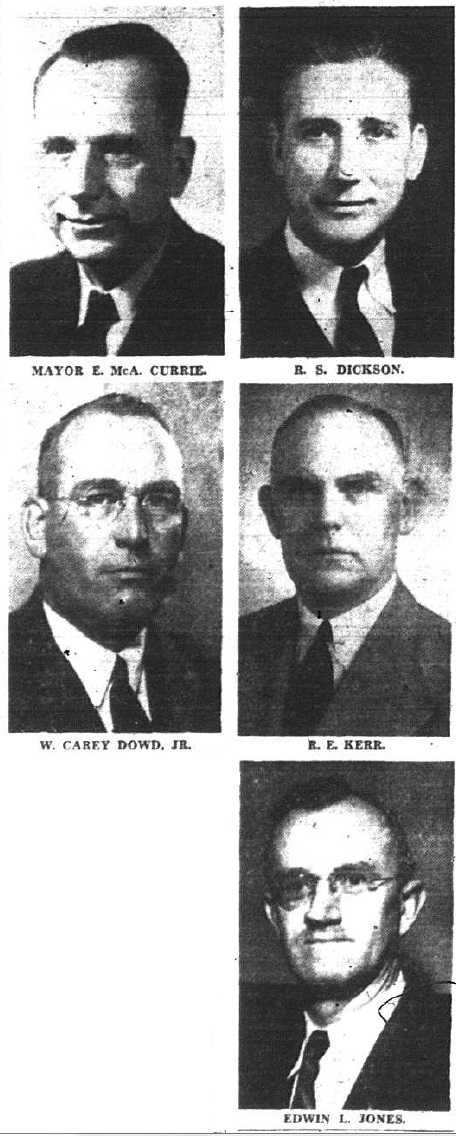

Charlotte was interested in doing business with the government for the benefit of the entire region. On March 3, 1942, 25 political and business leaders of Charlotte met at the Hotel Charlotte to investigate the possibility of persuading the U. S. Rubber Co. to build a plant near Charlotte. From this group, a planning committee was formed, and Mayor E. M. Currie served as chairman. This committee, also known as the Charlotte Industries Committee, consisted of R. S. Dickson, W. Carey Dowd, Jr., Edwin L. Jones and R. E. Kerr. [2]

After coming up with a recruiting plan, a group went to Washington to meet with government officials and business leaders who were interested in massive expansion of industry. The Charlotte Chamber was not asked to finance these trips to Washington to help establish businesses in Charlotte. Private funds were solicited and personal time was devoted to the projects. George M. Ivey [3], president of the Charlotte Chamber at the time, was pleased that so much was accomplished at such a small price. Former Mayor Ben E. Douglas [4] was asked to be the emissary to Washington to see that more efforts could be made on the current mayor’s behalf.

Their efforts paid off! Officials were impressed with Charlotte’s location in the South and its labor supply. The committee’s organized effort to locate the company in Charlotte was a success.

Sanderson & Porter, a well-known construction firm in New York, handled construction of the plant. Construction was completed in January of 1943 at a cost of $20,000,000. Thomas E. Clark was hired as the plant manager.

Representatives of the Navy, railroads and contractors as well as company officials of the U. S. Rubber Company, were officially greeted by a dinner at the Hotel Charlotte on February 18, 1943. The Charlotte Chamber of Commerce, which had more than 500 members at that time, sponsored the dinner.

During the height of production, U.S. Rubber Company employed several thousand people and had over 200 buildings in Charlotte. Its function was to produce 75 millimeter anti-aircraft shells for the Navy. After the war, it was a reclamation center for Navy salvage.

By the end of the war, the plant covered over 2,000 acres. It had its own water and electric lines as well as its own sewer system and was suitable for industrial use. In many ways, it was a city unto itself. The plant had gone from hand loading to assembly line processing and had great speed and safety records. It received the Army-Navy “E” award of excellence in April 1944 and two other times before production ended. Its peak day of production was December 6, 1944, when it produced 213,143 rounds in 24 hours.

A testing ground was established at a Wateree pond in South Carolina. Test batches of finished rounds were shipped there by truck. If they were acceptable, the entire batch was sent to the Navy by train. This process continued until the Navy cut back their production in July of 1945. Within two days after the end of the war with Japan, the contract between the government and the U. S. Rubber Co. was cancelled. By November, the last of the contractor’s employees were removed, and the plant became a naval ammunition depot.

By 1950, most of the buildings had been redone for postwar purposes. The hospital had been turned into a Marine barracks. The Marines were responsible for fire safety and security at the facility. The employment building had been converted into apartments. Civilians continued to work at the plant in administrative, maintenance and other support positions.

The “Shell Plant” does not exist today, but the area still remains mostly industrial.

“Rosie the Riveter”

During World War II, the plant became one of the biggest employers in the county, particularly in the employment of women. These women were Mecklenburg’s equivalent of “Rosie the Riveter.” In a recent interview, Dorothy Elizabeth Hood Terry, who worked in the prime and firing pin area #7, said in order to get a job, you had to apply and take a test. The majority of the employees hired were women, but supervisors were usually men. The men were also responsible for picking up the completed boxes for the women to inspect for quality. Because so many jobs were available, people moved to Mecklenburg County to work at the plant. The money was good, particularly for women, many of whom had never worked outside of the home.

Each piece was made in a different part of the building. They traveled through the buildings on conveyor belts. Employees worked around the clock. Shifts, which were 7 a.m.-3 p.m., 3 p.m.-11 p.m., and 11 p.m.-7 a.m., changed each month.

This was an extremely dangerous place to work, and the employees took their jobs seriously. There was no recreation on the premises, which was different than the activities at Morris Field. Remarkably, there were very few accidents. No rings could be worn on the line as a safety precaution. Employees were required to wear steel-toed shoes, navy blue skirts or slacks and light blue shirts. Without this type of uniform, you could not get on the premises to go to work. Employees had photo IDs that were pinned to their shirts while at work.

There were air raid drills, which meant employees had to report to the cafeteria to “wait it out.” There were catwalks from work areas to the cafeteria, and each area had its own cafeteria. Employees could bring their own lunch, but they had to eat in the cafeteria. Meals were served around the clock. Dressing rooms with lockers that were separate from the production area were also provided for employees.

Several men and women were on security patrol and carried guns at their sides. They protected the premises by walking as well as driving around. To travel within the area, you had to ride a special bus. If you drove to work in a car, you could only drive it to the area where you worked. Overall, employees felt very safe and protected. No photographs were to be taken on the property.

The employees were proud of their record and their contribution to the war effort. The money that they made and the job skills that they learned were invaluable to themselves and the community.

For more information about the “shell plant,” please read:

- “U. S. Rubber Company Gets Official Welcome Tonight…Rubber Plant Is Fruit of Co-Operation” by Henry Dougherty, The Charlotte Observer, February 18, 1943, page 1-B

- “Charlotte’s ‘Shell Plant’ Vital in War and Peace,” The Charlotte Observer, February 28, 1950, p. 18-J

- “Navy Depot’s Future Still Has ‘String’” by Emery Wister, The Charlotte News, March 7, 1957, p.1-B