Beatties Ford Road - 1990 [1]

CHARLOTTE CORRIDOR SYMBOLIZES TRADITION

By Frye Gaillard

Adapted from the Charlotte Observer, June 8, 1990

Beatties Ford Road – The River of Life

It is Sunday morning on Beatties Ford Road.

The street itself is nearly empty, but the parking lots are full at Friendship Baptist [2], Memorial Presbyterian and most of the other churches that line this corridor.

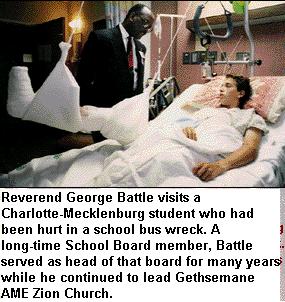

At Gethsemane AME Zion [3], the Rev. George Battle [4]’s voice soars above the amens. “What kind of life is this?” he shouts. “We see young men in fast cars, living fast lives in the dens and the dives, robbed by drugs of their physical energy and spiritual power - and sometimes they cry, What kind of life is this?’ “

To attend such a service is to understand the fundamental contradiction of Beatties Ford Road. For Charlotte’s black community it is a symbol of strength, lined with churches and schools, a university and neighborhoods with sturdy houses and families struggling to build a better life.

But fear intrudes these days, and you can hear it even in the sermons and the prayers.

Beatties Ford Road, at its southern end, runs through the heart of a neighborhood [5] with problems - an area where, in the first four months of this year, 935 crimes were reported.

One of the most spectacular came the night of March 30, when eight young men with guns lined up three others against a wall at Northwest Middle School. Apparently enraged by a bad drug deal, they opened fire, leaving three victims bleeding and lucky to be alive.

Even police were shocked.

”This is like Chicago,” said Capt. Don Harkey.

“That’s about as cold as it gets,” said Capt. Howard Dozier.

But to many who live along Beatties Ford Road, and others familiar with its history, crime and drugs are not the whole story. Nor is a pattern of neglect from city hall, which westside activists blame for slowing development along the Beatties Ford corridor.

On its meandering journey of 15 miles, Beatties Ford has long been a symbol of tradition and hope. It spans the gaps from urban to rural, black to white, from landed gentry to urban underclass.

“In the richness of its history, it’s unparalleled,” says historian Dan Morrill of UNC Charlotte.

That history came up often last week in debate over a proposal to rename a 3-mile stretch of the road Martin Luther King Drive.

Even in predominantly black areas, the proposal is controversial – not because blacks are reluctant to honor King, but because of their long identification with the name Beatties Ford.

“It's the river of life [6] for the black community,” says the Rev. Clifford Jones [7], minister at Friendship Baptist Church [2].

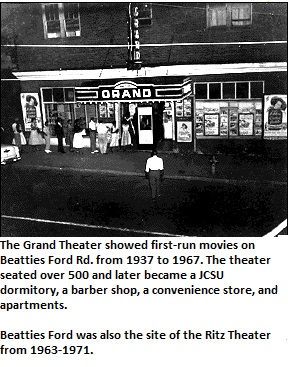

The road, named for Scotch-Irish pioneer John Beatty, begins at the crowded Five Points intersection, atop a hill where glass skyscrapers shimmer in the distance. To the right, beyond a brick wall and a cluster of oaks, rise the stately brick buildings of Johnson C. Smith University [8]; to the left, the boarded facade of the old Grand Theater [9].

From there, the road shoots north on a narrow, sometimes potholed course past some of the community’s most important institutions: the Excelsior Club [10], a longtime center of westside social and political activity; the United House of Prayer for All People [11], with services every night and five times on Sunday; West Charlotte High School [12]; McDonald’s Cafeteria [13] and motel complex, perhaps the best-known gathering place on the road.

For the most part, Beatties Ford is not a prosperous suburban artery, lined with a blur of fast-food franchises.

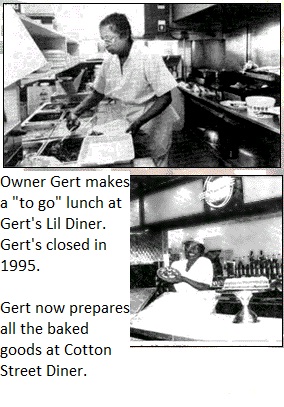

Its businesses are often small and locally owned: Gert’s Lil Diner [14], the Busy Bee Market, Skip’s Original Chicken and Ribs, Tena’s House of Charm [15]. A few of its corners have fallen hostage to drunks. Others are crowded with everyday people, gathering simply to visit or shop.

Somewhere north of I-85, beyond Gert’s and the bustling McCrory YMCA, the character of Beatties Ford begins to change. It moves slowly back in time until finally, just before it plays out on the shores of Lake Norman, it becomes a link to the 18th century.

White families have lived here for six generations, a few black families for nearly as long. Here, where cattle and show horses graze on the hills and deer occasionally bound from the woods, neighborhood leaders worry about development - the clash between urban and rural, and traditions lost to the spread of the city.

In the black neighborhoods [5] farther south, the fight is different – a struggle to sustain a tradition of progress that began more than a century ago.

“When I was growing up along Beatties Ford Road,” says Charlotte police Cmdr. L.R. Jones, “there was such a powerful sense of community. It was always a neighborhood. At some point in time, we started to lose that sense. Right now, we are struggling to get it back.”

Those struggles at both ends of Beatties Ford - one to preserve a neighborhood’s character, the other to restore it - are part of the continuing story of the road.

Most of the people leading the fight say they are sustained, in part, by a knowledge of the past - a sense of the meaning of Beatties Ford Road.

“There are problems,” concludes Clifford Jones [7], “but there are many, many strengths.”

JCSU - MAKING A DIFFERENCE

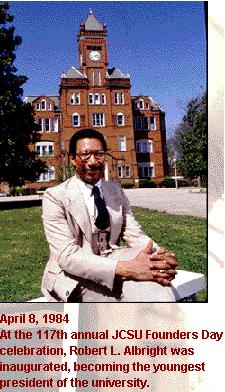

On a Friday morning at JCSU [8], the day is sunny, the campus quiet, and Robert Albright [16] is feeling reflective.

Albright is university president, a tall and ambitious man of 45. As he leaves his office and sets off across campus past a row of oaks, he talks about life on Beatties Ford Road and his institution’s attempt to make a difference.

Among other things, he says, JCSU offers after-hours classes for adults in the neighborhood and classes every other Saturday for children and their parents. JCSU honors students must work as tutors or commit to other community service, and the university is involved in Project Catalyst [17].

“I see a broad, tree-lined street,” he says, “with thriving businesses that provide economic opportunity. We have to provide an alternative to drug traffic, and show young people there can be other heroes.”

Albright is excited about that effort, and he believes it’s appropriate for his school to play a role.

For more than 100 years, JCSU - a private, historically black college with more than 1,200 students - has anchored the southern end of Beatties Ford Road.

On April 30, 1884, more than 800 citizens, black and white, drove theirwagons to a hill north of town, rumbling to a stop on the grounds of newly finished Biddle Hall.

It was the college’s first permanent building - a soaring, red brick structure on the city’s highest hill - dedicated as a working monument to the future of blacks.

Almost immediately, a community of black teachers, ministers and other professionals grew up nearby, and by the early 20th century other black suburbs began to appear along the road.

For the next 50 years, Beatties Ford was a prestigious address for black Charlotteans.

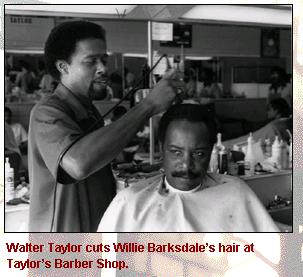

Walter Taylor [18], 48, who runs Taylor’s Barber Shop at Beatties Ford and LaSalle Street, grew up in the area. He remembers evening walks to the Grand Theater [9] or the Varsity Grill, both now gone, when the greatest hazard for a child was an old lady’s scolding for stepping on her flowers.

“It was such a beautiful area,” he says, “and some of the homes are still very nice. But today when I get off work I go straight to my car. If I had to walk a block down the street after dark, I’d be very leery. People don’t seem to know each other any more. They don’t seem to care.”

George Cunningham agrees.

Cunningham is retired after working 20 years for the City of Charlotte. At 79, he spends most afternoons when the weather is nice sitting on his porch overlooking Beatties Ford Road. He and his friends settle themselves into straight-backed chairs, and sometimes they talk about the state of the road.

“This is a pretty good area,” Cunningham says. “When I first started living here, I guess it’s been about 18 years, you could walk the road at 12 o’clock at night, and never think a thing about it.

“But I wouldn’t do that now. You have different type of people coming in and out.”

CHANGING TIMES

The police car cruised down the unlit alley, barely a block off Beatties Ford Road, just north of I-85.

Charlotte Officer A.L. Briggs gestured out the window toward a battered white house. The screen door was ripped, and the light inside was dim and alluring.

“There,” said Briggs, “that’s a liquor house. You can get anything you want in there.”

Briggs meant drugs.

Police say buyers come to the area from as far as South Carolina to get cocaine and other narcotics. Last year, police made 195 arrests for the manufacture, sale or possession of drugs in a 3-mile corridor along Beatties Ford. Gene Bell worries about the drug problem.

Standing in the parking lot of his Beatties Ford office, about a mile north of JCSU, he gestures toward a group of men on the corner. It is a Monday evening, a few minutes after 9. Some of the men are drinking; one or two appear to be in a stupor against the wall.

“A lot goes on on these corners,” says Bell. “It wouldn’t be tolerated in another part of town. . . .It seems like nothing is done about black crime.”

RECLAIMING THE COMMUNITY

They know it’s not just a black - or Beatties Ford Road - problem, but community anxiety is high. Preachers preach about it on Sundays, and in community gathering places like McDonald’s Cafeteria or on the bulletin boards at JCSU, flyers announce community forums.

“Stop The Killing,” one proclaimed last month. “Nobody can save us from us but us.” It was one of many signs the community is fighting back.

At Northwest Middle School, where bullet holes still scar the brick wall at the back of the gym, Principal Rosalind Rowe-Anderson moves ahead undaunted.

“It’s a shame it happened here,” she says, “but it really didn’t have much to do with us. The kids weren’t that bothered. I heard one of them say, Well, I guess we’ll have to fix the bullet holes.’ “

Rowe-Anderson points with pride to Northwest’s spotless, litter-free campus, its neatly trimmed lawns and freshly painted walls, devoid of graffiti. Some of Northwest’s buildings are more than 50 years old, but the school staff works to keep them in shape. Rowe-Anderson says she owes it to her 500 students in grades 6-8 - and to the area around her.

“In this neighborhood,” she says, “it’s so important how the school looks. We want to be a part of this community. It seems like everybody has come through here. This used to be West Charlotte High School.”

She utters the last sentence with pride. West Charlotte, which has moved to a campus a half-mile north, was once one of Mecklenburg’s elite black schools. For people such as Rowe-Anderson, who see great hope for Beatties Ford Road, the legacy of strong institutions is critical: the schools, the churches, the university and a growing string of businesses intended to serve as models of success.

A COMMUNITY INSTITUTION

Lunchtime approaches at McDonald’s Cafeteria [13].

Already the parking lot is beginning to fill, as John McDonald [19] moves through the kitchen to the clatter of pans and the smell of chickens beginning to cook - the first of 300 they’ll prepare that day.

“It’s going to be a good day,” he announces to his staff, clapping. “We’re gonna cook some good food today.”

A gregarious, deeply religious man of 69, McDonald introduces himself to patrons as “the cook.” But he is in fact the owner, and his business at I-85 and Beatties Ford Road is one of the most prominent in Charlotte’s black community.

He tells his story unselfconsciously: He was running a successful dining hall in Brooklyn, N.Y., when God told him in a dream to go home.

“I did what He told me to do,” McDonald says.

Now, his cafeteria, which serves nearly 2,000 people a day from all over the city, and its adjacent, 105-room hotel have become a westside community institution.

“It belongs to the people,” he says. “It helps to give them a sense of belonging, creates jobs - and creates a role model for this community. All up and down, not just here, we see more new buildings on Beatties Ford Road. This is a sign of what people can do.”

(John McDonald died October 26, 1995)

BUSINESS DEVELOPMENTS

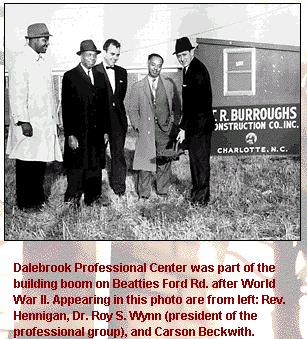

Other westside businesspeople agree, pointing to such developments as Krystle Village shopping center, Cummings Retail Center and the Dalebrook Professional Center [20], all just south of I-85.

“We’re going to see a renaissance,” says Nasif Majeed, treasurer of the West Trade Beatties Ford Area Merchants Association.

Sam Young, a black real estate developer and founder of this weekend’s Westfest neighborhood celebration at West Charlotte High, believes a business renaissance - with the visible symbols of progress it provides - is critical to the future of Charlotte’s black community.

“For the kids,” he says. “The more they see what we can do, the more they understand and believe it.”

Laura McClettie [21] shares his vision.

As executive director of the West Charlotte Business Incubator, an effort to encourage new business in the Beatties Ford area, she believes the key to the future is economic.

“Right now,” she says, “I live on the east side of town. But I want to move back. The other day, I was riding down Beatties Ford Road with my son, and I said, I just love it.’ He said, Yeah, but how are we going to deal with the killing and the crime?’

“He is 11, but already that’s what he sees. It seems to me we have to do something. We have to fix that. We have to do everything we can to take care of our community.”

It’s important, McClettie says, to create thriving new businesses so young blacks, particularly males, can see an alternative to the world of drugs. “Druggies don’t gravitate to beauty or life. They gravitate to where things are dead.”

SENSE OF KINSHIP

In the 15 miles from JCSU to the brambled shores of Lake Norman, Beatties Ford Road is not a single neighborhood, but a series of communities tied together by the road.

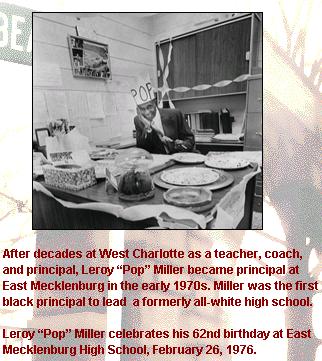

From Biddleville to McCrory Heights, Hyde Park to Long Creek and Lemley, smaller neighborhoods have developed their own leaders, tireless people like Leroy “Pop” Miller [22], Louise Sellers [21] and Christine Parks.

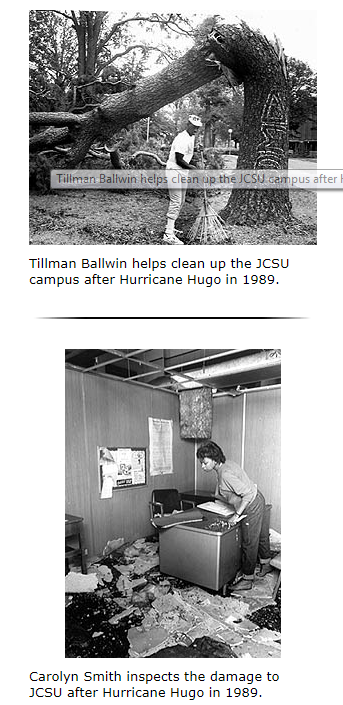

Miller, a former Charlotte educator who lives in the Dalebrook [20] section south of I-85, and Sellers, who has lived most of her 61 years in the Biddleville-Five Points community, believe their part of the road has been neglected. They tick off such problems as broken sidewalks, piles of litter they can’t get picked up or Hugo debris [23] still on the ground.

They talk about absentee landlords who neglect their property and charge high rents, and housing codes that go unenforced.

When officials proposed a garbage transfer station on LaSalle Street, not far from Beatties Ford, Miller [22]organized a Westside Coalition of 10 neighborhoods to sue. They defeated the plan.

Some westsiders say the victory was a turning point, sparking new optimism about the future of Beatties Ford - and more respect for that corridor in the halls of local government.

For many neighborhood leaders, meanwhile, a deepened sense of kinship remains.

“All these issues are important,” says Christine Parks, a white activist who crusades against haphazard commercial development in the Long Creek area. “We try to support each other when we can.”

Allan Smyth believes that’s appropriate.

For six years, he has been the minister of Hopewell Presbyterian Church, which began its life in 1762 near the northern end of Beatties Ford Road. Surrounded by a gray fieldstone wall and a cemetery dating to the 18th century, it remains a link to Mecklenburg’s colonial past.

In that kind of setting, says Smyth, it is easy to become a student of history - and the black and white histories of Beatties Ford Road are like two great, converging streams that continue to flow.

Sometimes, Smyth gazes out the curtained windows of his study, past the fading gravestones and the grove of cedars, magnolia and oak.

He can see the curve of Beatties Ford Road, with its aura of old ghosts and the complicated problems of today, and he lets his imagination run free.

“I see Indians,” he says, “and I see Cornwallis and Red Coat soldiers. I see the gold miners and the early colonial settlers, and I see the slaves who once sat in the balcony of this church moving a mile up the road to start a church of their own.

“For a whole lot of us,” Smyth concludes, “Beatties Ford Road is a link to who we are.”

The African American Album: The Black Experience in Charlotte and Mecklenburg County. Vol. 2. Charlotte, NC: Public Library of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County, 1998. Computer optical disc, 4 3/4 in.