Chapter 4 [1]

THE CHARLOTTE CHAMBER OF COMMERCE considered the greatest problem concerning Camp Greene to be convincing the government to locate it in Charlotte. Unfortunately, a greater problem was the failure of mother nature to cooperate with the government and Charlotte. Major problems surfaced early in the camp's development and hosts of minor problems arose immediately. The sudden influx of troops caused crowded living conditions in the finished areas of the camp. One soldier's father complained that eight or nine men occupied his son's tent. It was army policy that no more than five men were to share quarters. This situation and similar minor problems were investigated and adjustments made with relative ease. If all problems could have been so easily remedied, camp life would have been a totally pleasant experience. More serious problems proved difficult to cope with, and yet were handled admirably by all concerned.

Conditions of access roads from Charlotte to the camp were a lingering problem. On January 1,1918, Major Kaempfer completed a report to the War Department on the conditions of the roads and highways connecting the city to the camp. He made specific reference to the promise representatives (from Mecklenburg County and Charlotte Township) and municipal authorities had offered as an inducement to locate the camp in Charlotte. These men had vowed that roads "a class satisfactory to the military authorities would be constructed without unnecessary delay." As early as August 7, 1917 the roads had not been repaired and were in worse shape than when the promise had been made. Indications were the roads would remain in disrepair.

The trouble was a difference in the interpretation of the promise between W. R. Matthews (chairman of the Charlotte township road trustees) and Thomas Griffith. Mr. Griffith wanted to fulfill the promise to repair the roads, spending some $20,000. Mr. Matthews only wanted to "clean out the ditches and scatter the dirt and ground on the surface filling up the holes." Mr. Griffith stressed the negative reflection on Charlotte as it would appear a promise had not been kept. Under pressure from the city as well as the army, the trustees voted unanimously to borrow $20,000 to repair the roads. Although some work was done, it was not nearly enough. Only two highways connected the city and the camp. Repairing one meant the other would have to bear the enormous military and civilian traffic. It was considered an urgent matter that both roads be developed into main arteries of military highway class.

The surface work on the Tuckaseegee Road had to be completed from the base hospital to a point about 100 yards across the Piedmont and Northern Railway. The work had been suspended for a month and during that time the road had been completely closed to traffic. This necessitated the routing of all traffic from the hospital and Camp Greene headquarters to the city over the already congested Dowd Road to Charlotte. The Dowd Road was described as "absolutely dangerous," including a blind grade crossing, four bad turns and a very rough surface. After completing these "adjustments," the surface was still considered unsatisfactory.

The new roadbed was considered too narrow as the width (about twelve feet) did not allow vehicles to pass without one or both leaving the paved surface. The condition was aggravated by the fact that a vehicle leaving the pavement was forced to take a quick drop of from six to eight inches because of the elevation of the paved surface. Considering the amount of military traffic using the surface, continued destruction of the paved surface was assured. The elevated edges of the paving would be crushed under the huge wheels of the loaded army trucks travelling at rapid speed.

Additional repair work was not high on the priority list of Charlotteans but it was clear that such conditions would become important in determining the future permanency of Camp Greene. While there was no fear that the camp would be removed before the end of the war, there was no assurance that Camp Greene would be maintained as a permanent base. Realizing the seriousness of the situation, the Charlotte Township road trustees gathered in the county courtroom and voted unanimously to petition the Board of County Commissioners to levy a special tax upon the citizens of the township. The purpose of the tax was to raise funds to improve the Dowd and Tuckaseegee roads to Camp Greene. A tax of ten cents on every $100 was levied upon the property owners for three years. This measure raised $28,000 the first year and about $82,000 over a three-year period. The estimated cost for the improvements and repairs for the roads amounted to between $75,000 and $85,000. The government then announced it would spend $80,000 to build the roads within the camp.

Fires were another problem. Most were small tent fires started by faulty stoves and resulting in the loss of only a few personal possessions. There were two serious fires which resulted in extensive property damage but no lives were lost. The first fire involved a portion of the base hospital including the laboratory and operating room buildings. It was attributed to a defective flue which "for some reason" escaped detection by the soldier "detached as watchman." Since the fire occurred on December 31, 1917 it has been speculated that some New Year's Eve celebrating might have been the cause. Frozen water mains hindered the fire fighters. Approximately 900 soldiers who were patients in nearby wards were miraculously saved by the lack of wind. The blaze was brought under control with the aid of firemen from Charlotte. Both the lab and the operating room were total losses representing at least $75,000 in damages.

On April 10, 1918 another major fire occurred at the national YMCA Hostess House. Earlier that day a large group of between 200 and 300 soldiers had been entertained in the building. The flames came from the furnaces under the floor of the big living room. Three secretaries declared there was but a small fire in the room when they retired for the night. The building was wooden frame and highly flammable. High winds fanned the flames and quickly reduced the building to ashes. "Spontaneous combustion" was the stated cause of the fire.

Health problems became one of the more serious matters faced by the staff at Camp Greene. The tremendous population of the camp made the organization of a health department mandatory. The United States Public Health Service sent Major B. W. Brown to oversee the organization. Dr. C. C. Hudson was appointed health officer taking charge in October 1917. The staff included a part-time milk inspector, a part-time clinician, one sanitary inspector and two nurses for general work. Major Brown and Dr. Hudson acquired assistance from the Red Cross who sent four field nurses and one nurse superintendent. Later a nurse assigned for follow-up work in venereal disease and a Negro nurse were appointed. This unit worked closely with the medical staff of the camp.

Medical services for the soldiers were provided by the Base Hospital which accommodated 1,000 patients. All the buildings were well-heated by stoves, with steam heat in the two operating rooms. Plumbing and sewerage were installed at a cost of approximately $50,000. The huge facility had a section for recreation of the patients (including pool tables), shower baths, a tailor shop and a barber shop. Commanding officer Major W. L. Sheep supervised every aspect involved in running the hospital, described by some as a "complete little city within itself."

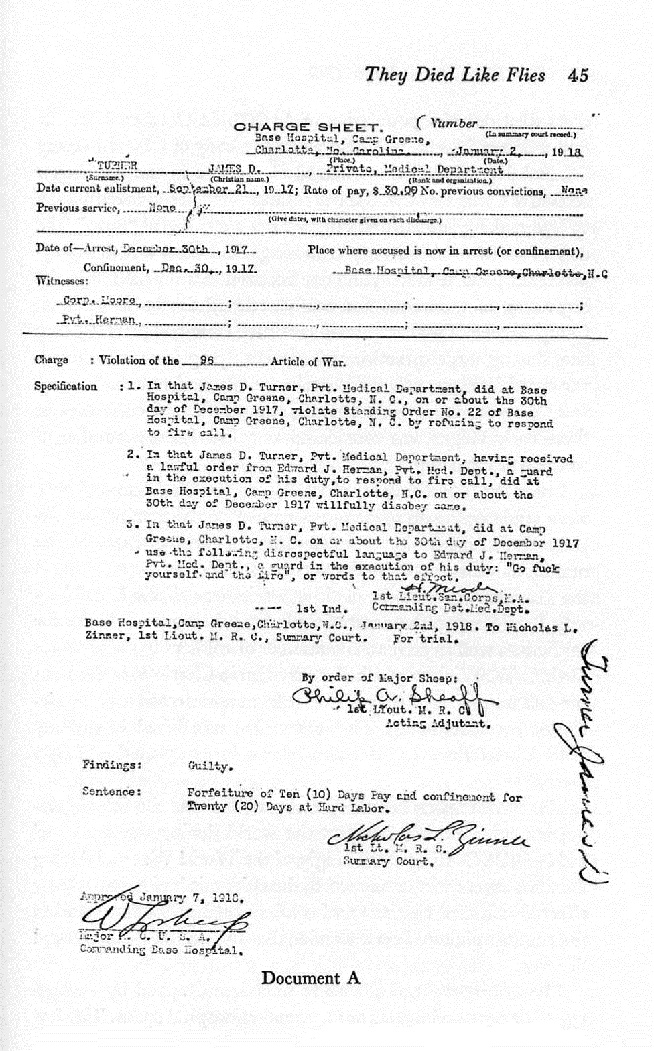

[See example of a write-up for disciplinary infraction at Camp Greene [2]]

In the first three months of the camp's existence only five soldiers died out of a population of 14,000. In October 1917 the first military funeral was held when the body of Captain Henry Stiness' dog "Tobe" was lowered in a grave in the warehouse section of Camp Greene. A file of infantrymen fired the regulation volleys and a good-natured bugler blew a sorrowful "taps." The dog's funeral with military trimmings had been a heartily appreciated joke. Ironically, no one realized this marked only the beginning of numerous non-combat-related deaths to occur at Camp Greene. Two early deaths resulted from one private being shot during target practice and another dying of pneumonia. A variety of diseases such as diptheria, measles and venereal disease were also common. Nevertheless, the number of casualties in these early stages was considered very low for the number of soldiers at the camp.

In January and February of 1918, Charlotte and Camp Greene were subjected to an epidemic of cerebrospinal meningitis. Experts were sent to the camp to assist in the treatment of the numerous cases and to educate the soldiers in how to avoid the disease. A quarantine of three weeks was effected, and Liberty Park (a popular recreational area) became off limits for soldiers as well as civilians. A number of soldiers in one division died. A. W. Wicker was the first civilian in Charlotte to die from the disease probably contracting it from an infected soldier who visited his barbershop. The quarantine was lifted in the city after a brief time, but remained for a longer period at Camp Greene.

The most serious health-related problem was the Spanish influenza epidemic which swept the world during the winter of 1918-1919. Coming at the height of the World War and during the most severe winter on record, the epidemic had a devastating effect. It afflicted civilians and soldiers both at the front and in the camps at home. It is a wonder that the flu itself did not end the war.

The townspeople of Charlotte were handicapped by a shortage of doctors and nurses not to mention hospital space. The few in charge were swamped with work during the height of the siege, often making over 100 calls a day. Because of the disorganization of the health department, no record of the total number of cases or the death rate was kept. The exact toll will never be known. It is estimated that over 40,000 of an approximate population of 80,000 were infected. One doctor estimated a three per cent death rate, or a total of about 1,200 in Charlotte alone.

Camp Greene added to the horror. There were so many deaths among the soldiers that the undertakers were swamped. At one establishment, sixty bodies were stacked awaiting some semblance of a funeral. Charlotteans remember coffins "stacked to the ceiling" at the railway station waiting for trains to take them home. There were daily processions down Trade Street accompanied by the drumming, sad, slow cadence of the funeral march. Unclaimed bodies were buried in Elmwood Cemetery and marked with crosses like those on the graves in Flanders.

The virulence of the infection and the frequency of pneumonia caused the patients' resistence to diminish rapidly. The onset was sudden and overwhelming, often claiming its victim within twenty-four hours. Mrs. Lucy Shelby recalls spending a pleasant Saturday night at a dance with a young soldier who made arrangements to meet her the following week. When the day came, another young man appeared in his place saying the other solider had told him to keep his date for him. He explained that his friend had been "struck with the flu" and had died on Wednesday. The disease gave no warning and had no regard for rank. Almost daily the newspaper reported the deaths of officers, nurses, volunteer workers and enlisted men.

In an effort to retard the spread of the Spanish influenza, a strict quarantine was declared between October 4 and October 15, 1918. Schools, churches and theaters were closed and all public meetings were forbidden. One necessary meeting of the Chamber of Commerce was held with members wearing flu masks. A new law provided: (1) no person who had the disease could leave the premises until after the seventh day from the onset of the disease; and (2) no child living in a diseased household could leave till after the twelfth day of the onset of the last case. No spitting was allowed on public streets. Penalty for violations of any provision of the law was a fine of fifty dollars.

The closeness and draftiness of the tents enhanced the rapid spread of the flu. Certain steps recommended to keep the flu from developing were difficult to carry out in the camp environment. The men were urged to go to bed. Purgative medicine was to be followed by a dose of quinine and aspirin and repeated every two or three hours. These precautions were seldom followed until a man was actually infected. By then it was usually too late. "Proper" tonics (including cod liver oil) were considered valuable. One of the most popular tonics "Tanlac" was sold in great quantities in Charlotte by wholesale as well as retail agents. In January 1919 it was reported that 57,612 bottles had been sold.

The role of the Charlotte chapter of the American Red Cross in Camp Greene was very important. Established in March 1917, the new and enthusiastic group provided such things as "delicacies for sick soldiers," extra blankets and warm clothing. They sponsored a "home service" program to board wives accompanying their husbands to camp. Since there was no affordable place for them to stay in the city, this was a much needed service. During the flu epidemic, the work of the Red Cross was particularly invaluable. Contributions made by this group were: a recreation room, 20,000 sweaters given to the men in one month alone, 597 refugee garments made, 163 pairs of socks mended, 171 bandages rolled and 186 garments sent to the Base Hospital. The Motor Corps Service reported 1,148 miles, or 241 hours were driven in one month for the Red Cross. Eleven thousand nine-hundred and ninety-one men in uniform were serviced during one month alone.

Besides dealing with epidemics and specific medical problems, the health care at Camp Greene included general preventive and educational health services. Frequent lectures were given on every subject from sex hygiene to foot care. Numerous psychological tests* were given to determine which task in the military framework was best-suited to each soldier. (*The tests were of two classes, the Alpha test for those with the ability to read and write English, and the Beta test for those who could not. Individual tests were given for those who did not fit into either category. Lieutenant E. M. Chamberlain was the head of the psychological examining board.)

Sample of Results of Mental Tests

White Recruit Camp 8, Co. 2

Very Superior (A) 2 - 1%

Superior (B) 4 - 2%

Average (C+) 17 - 7%

Average (C) 45 - 17%

Average (C-) 62 - 24%

Inferior (D) 80 - 31%

Very Inferior (E) 47 - 18%

White Recruit Camp 5, Co. 3

Very Superior (A) 1 - 1%

Superior (B) 5 - 2%

Average (C+) 9 - 4%

Average (C) 27 - 9%

Average (C-) 43 - 19%

Inferior (D) 91 - 36%

Very Inferior (E) 73 - 29%

Black Recruit Camp 5, Co.1

Very Superior (A) 0 - 0%

Superior (B) 3 - 2%

Average (C+) 12 - 6%

Average (C) 45 - 17%

Average (C-) 52 - 27%

Inferior (D) 78 - 41%

Very Inferior (E) 13 - 7%

Black Recruit Camp 5, Co.3

Very Superior (A) 0 - 0%

Superior (B) 0 - 0%

Average (C+) 5 - 3%

Average (C) 22 - 14%

Average (C-) 33 - 21%

Inferior (D) 60 - 38%

Very Inferior (E) 40 - 25%

A battery of tests were given the troops almost immediately upon their arrival in Charlotte. There were eight tests requiring powers of concentration, quickness of thinking, good judgment and some knowledge. All enlisted men, non-commissioned officers and command officers below the rank of major were required to take the exams. One series of tests measured the mental abilities of the troops. The results ranged from highly intelligent to illiterates. The purpose of these tests was primarily to eliminate the mental incompetents who might seriously affect the good of the service. Camp Greene (like all military bases) contained a cross section of the population. The military drafted men from all walks of life and the standard tests most likely failed to consider the various cultural backgrounds of these recruits.

The tests were considered of great value to the army and at the time was an effort to insure the best care for all men regardless of rank or ability. However, from a contemporary viewpoint the interpretations of the tests reveal a degree of racial, political, cultural and nationalistic bias. In some cases men were declared unfit to serve and removed from service on the basis of the tests. The following examples were taken from the psychiatric records:

Machine Gun Co. 59th Inf.

Dickerson, J. F., Cpl. - Dizzyness, headaches, and loss of sight began about six weeks ago, sees imaginary discs, at times everything seems white, eyes constantly water, tremor in hands, hysteria

Co. A, 59th Inf.

Baerngen, A., Bugler Constitutional psychopath, lacks moral sense, has been arrested in civil life for drunkenness, is presently under arrest for disobedience

Gardino, J., Pvt., Mental deficiency, cannot understand and execute demands

Kriezell, I., Pvt., Constitutional psychopath, untruthful, obstinate, unreliable

Co. B, 59th Inf.

Bronteno, J, Pvt. Syphilitic, slow, dull mentally, on sick call constantly, inadequate for service, is a barber or shoemaker

Angelica, L., Pvt. D.M.D., constantly violates discipline, has been caught in Negro district time after time

Gearing, F., Pvt. Marked nervous tremor of the head, hands and tongue, has had syphilis, is steel worker

Hodnett, W., Pvt. Staggers when he walks, marked swaying with eyes closed, defects mental development

Karachoon, A., Pvt. Complains that his head bothers him, nervous, violator of discipline, is a farmer

McGill, F.,Pvt. D.M.D., cannot be taught, is a moron, cannot remember orders, is a farmer

Co. C, 59th Inf.

Rodgers, J., Pvt. Bedwetter since childhood

Yacuric, D., Pvt. Small, undersized, cannot be trusted with responsibility, inadequate for line service

Tomasini, R., Pvt. Defective English, is slow to comprehend, muscularly inadequate, D.M.D., moron, peculiarities of attitude, heavy drinker

Co. D, 59th Inf.

Knight, Ebon R. Pvt. Constitutional psychopath, inadequate personality, is dumb, a boob, can't march, slow to catch on, forgetful

Co. E, 59th Inf.

Steins, Frank, Pvt. Conscientious objector, is an Austrian, does not want to fight against Teutonic powers, not a citizen, left Austria to avoid service

Thornton, Elihu Pvt. No education, disloyal, does not want to fight because Americans are wrong, inadequate for foreign service

Metz, John, Pvt. Born in Austria, is considered pro-German, inadequate and dangerous for foreign service

Besides health problems, the most persistent problem that plagued the camp was bad weather. Charlotte was noted for its mild winters with temperatures rarely falling below 35 degrees and averaging 40 degrees, and a yearly rainfall of only 49.20 inches. Unfortunately, the men at Camp Greene experienced untypical weather in the fall and winter of 1917 and 1918. As early as September 1917, the daily forecast read heavy rain. Rain continued for several days drenching the ground and converting it to thick mud. The heavy traffic over the principal military thoroughfares contributed to the problem. The mud -- a novelty to the soldiers at first -- soon became a perpetual nuisance. Conditions worsened with time, aggravated by the continual rainfall and the passage of more and more soldiers. The roads became impassable as the wagons and motor vehicles ground deeper ruts into the surface. The blowing, biting cold winds and intermittent sleet storms added to the already extremely hazardous road conditions.

Charlotteans witnessed "the worst winter we have ever had, before or since" in 1918. Cold temperatures, blizzards and icy winds characterized the weather. Each tent was supplied with a stove and the men were given warm clothes and blankets. Enormous quantities of wool clothes arrived periodically from the War Department. One shipment alone consisted of 100,000 pairs of shoes, 80,000 pairs of wool breeches, 130,000 flannel shirts, 60,000 pairs of gloves and 60,000 suits of heavy wool underwear. Thousands of cords of wood were scattered throughout the camp and huge piles were kept at each company mess hall. "All we have to do is go and get it," answered a soldier when asked about the availability of wood in early November 1917. Within a few weeks, however, the camp was faced with a serious wood shortage continuing throughout the winter. Each day soldiers hastily gathered wood to meet the night's needs and hopefully to last a few extra days. Only green wood was available and it proved unsatisfactory because it burned too slowly and produced little heat. The men experienced periods without warm water and often without regular baths.

Deep snowfalls brought training to a standstill and delayed construction of the trenches. However frustrating the inconveniences caused by the adverse weather conditions were, they were not debilitating. The men made the best of the situation. For instance, one infantry unit was forced to sleep in the open because their tents had failed to arrive. They joked, put on two pairs of trousers, wrapped themselves in their blankets and ponchos and retired to bed. Some slept on the ground; others huddled up in the corners of the open-top boxes formed by the floors and side-walls of tents that had been removed.

When the snow melted, seas of slush and icy mud covered the area. Company streets became collections of puddles and patches of snow connected by inch-deep seas of slippery red mud. Despite insecure footing and oft-repeated ridiculous falls, the men went about tasks like cutting wood without accident. Real combat experience was gained when infantry units marched from the rifle range to Camp Greene over twelve miles of indescribably rough roads. Health problems and bad weather proved the greatest obstacles in training troops at Camp Greene. Flu epidemics, rain, wind and snow were totally unpredictable factors. In 1917, no one could foretell the sunny South would suffer hard winters and epidemics during the following years. These problems were competently handled by the officials of the army and the citizens of Charlotte. Camp Greene was as well staffed and equipped to meet the problems as any place could have been at the time. In spite of Mother Nature's lack of cooperation, Charlotteans and the army joined forces to make Camp Greene a success.

Miriam Grace Mitchell and Edward Spaulding Perzel. The Echo of the Bugle Call: Charlotte's Role in World War I. Charlotte, NC: Dowd House Preservation Committee, Citizens for Preservation, 1979.