The Great War

Historians continue to debate over the real causes behind World War I. One thing is for sure, Europe and Eastern Europe in particular were hot beds of political and social unrest in the summer of 1914. Resentments from previous wars, strong nationalism, and an accelerated arms race among all the European nations only heightened the atmosphere for war. Tensions were high especially in the countries under the Austrian Hapsburgs’ rule. The catalyst for the war that plunged nations into its first major World War was the assassination of the heir to throne of Austria-Hungary, Archduke Francis Ferdinand and his wife, the Duchess of Hohenberg on June 28, 1914 by Serbian anarchists. Austria-Hungary quickly declared war on Serbia and Russia entered the war on the side of the Serbs and France also allied with the Russians. Germany, who was an ally of Austria-Hungary's, realized the time was ripe to reclaim territory from France that it had lost in 1871 and invaded the French province of Alsace-Lorraine in August of 1914. England immediately joined sides with the French and the Russians. On May 7, 1915, German torpedoes sunk the British ship, the Lusitania. More than 100 Americans on board ship were killed.

Although these disturbing events were described in detail in local newspapers throughout the United States, as a nation we did not want to participate in any conflicts that did not directly concern us. The United States' foreign policy was one of neutrality. Old-world feuds and broken treaties among many European nations did not concern the average American. These incidents seemed worlds away for most Americans, including those in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina.

The American President

President Thomas Woodrow Wilson was determined to keep America out of the war at all cost. The son of a Presbyterian minister, Wilson attended Davidson College, a Presbyterian school in northern Mecklenburg County, in 1873 before graduating from Princeton University in 1879. He earned a law degree from the University of Virginia and a doctor of philosophy degree from Johns Hopkins University. Before becoming the 28th President of the United States, Wilson was an accomplished teacher, scholar and author. He later served as the President of Princeton University and was Governor of New Jersey prior to being elected to the highest office in the land in November of 1912.

President Woodrow Wilson was invited to attend the celebration of the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence [1] on May 22, 1916. He accepted the opportunity to come to Charlotte, join in the festivities and give a speech. Few would predict that day that the President and the country would plunge into the war in less than a year.

In February 1917, British intelligence purportedly uncovered a plot linking Germany with Mexico in a plot to invade the United States from its southern borders. Month later, German "U"-boats (submarines) sunk five American merchant vessels. Although Wilson had been re-elected in 1916 on the slogan, "He kept us out of war," the President could no longer ignore the facts that the war was now coming to America. Wilson requested the United States Congress declare war on April 2, 1917. The Congress complied by declaring war on Germany on April 6, 1917 and on Austria-Hungary on December 7, 1917.

The World at War

Countries chose sides and formed into two alliances known as the "Allies" and the "Central Powers."

Allies:

Belgium, Brazil, China

Cuba, France, Great Britain

Greece, Italy, Japan

Liberia, Montenegro, Portugal

Rumania, Russia, San Marino

Serbia, Siam, United States

Central Powers:

Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria,

Germany, Turkey

Other countries never declared war but were affected by the conflict due to their geographic locations or to the cut-off of diplomatic relations.

World War I witnessed a new age of new military strategies and inventions to fight one's enemy. Trench warfare was the name of the game as soldiers lived in endless, muddy confinement while waiting for the next attack. Snipers on both sides kept the troops well below the trenches. A whistle would blow to announce an attack. The soldiers poured out of their protective trenches and made their way across the battlefield, dodging bullets and incoming mortars. Then they had to cut through the barbed wire on the enemy's side in order to occupy their trenches. Little territory was gained or lost compared to the number of soldiers killed in each battle. Mustard gas and other poisonous substances became popular weapons of choice. If the gas did not kill the soldier immediately, he could be left blind or with irreparable damage to his lungs. The use of an "Airforce" debuted in World War I. The airplane proved to be perfect for dropping bombs, gathering intelligence and more importantly it took the war to the air as opposing pilots blasted away at one another in infamous "dogfights." Other modern inventions of war included tanks and trucks. The latter were converted to ambulances to carry away the wounded. However, the European battlefield was, for the most part, a quagmire of mud, pack animals continued to be the means for which both sides transported trucks and munitions. The conflict involved so many nations and destroyed so many lives and lands that it was thought to be the war that would end all wars!

Meanwhile in Charlotte

When it was learned that the United States military was looking for a place to build a training camp, the city fathers went to great lengths to convince the decision makers in Washington, D. C., that Charlotte was the best place to locate. Their efforts paid off, and a camp was built and named Camp Greene, after the Revolutionary War hero, Nathaniel Greene.

The rural area once used for growing cotton and vegetables was suddenly transformed into a major military facility. Thousands of men from across the country trained at Camp Greene. Tents and wooden barracks were erected, roads were built, and men and materials started pouring in by train. Local men, who were fortunate to be hired during the construction of the camp, found the pay was good, and the work was steady. However, some Charlotte businessmen were accused of raising prices in the anticipation of a boom in sales.

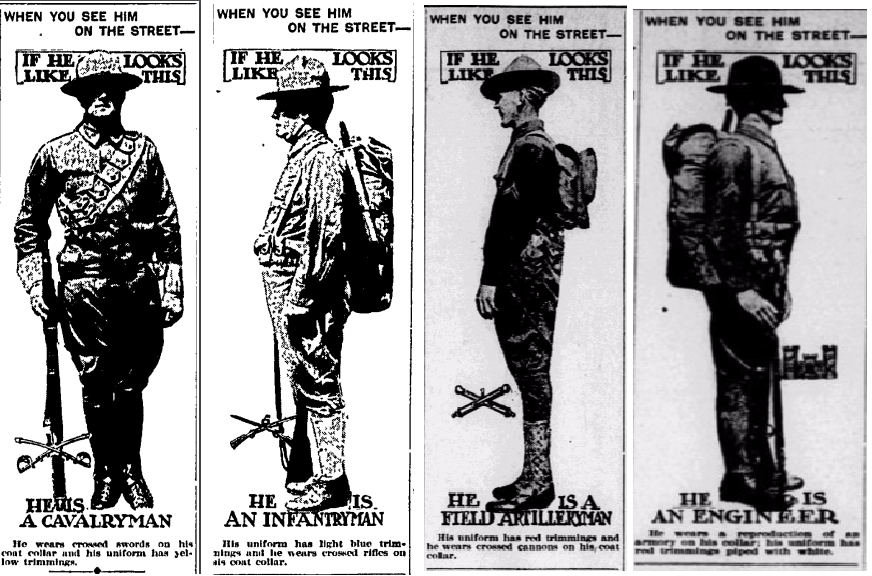

The residents of Mecklenburg were not familiar with the sight of so many military men in their area. Images of men in uniform [2] ran in the newspaper to teach local citizens the different types of soldiers and sailors that would be seen on the streets and roads.

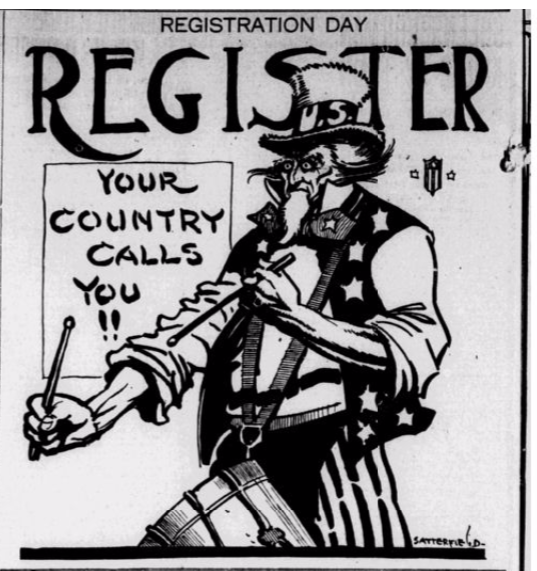

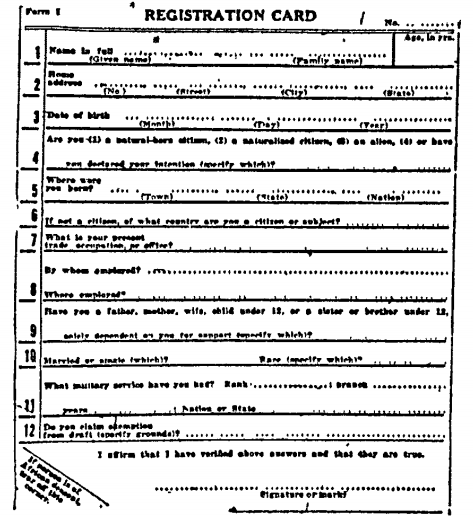

In order to fill the quota of the number of men needed to serve in the military, three draft registrations [3] were required during the course of the war. For the first draft, Charlotte Mayor Frank McNinch formed an advisory board with James L. Delaney, J. Lawrence Jones, and Dr. Otho B. Ross to hold the registrations. On June 5, 1917 [4], a parade was planned with the help of the Chamber of Commerce. All patriotic groups in the area were requested to participate. The lobby of the Buford Hotel in Charlotte was chosen as the site for the registration preparation. Space and lights were provided free.

All men between ages 21 and 30 were required to register. The punishment for failure to register was a year in prison. Charlotte had a good turn out with approximately 4,449 men registering! Khaki bands were pinned on the newly registered men's sleeves by a local young lady after they registered. The heaviest registration took place in the City Hall in First Ward. The Court House in Second Ward had the largest registration of African-American men.

As the war progressed; the age limit for registering for the draft increased to forty-five. However, there was no guarantee that any of the men would actually serve in the military. Some had physical, mental or emotional problems that prevented them from enlisting. Others remained at home because they were the sole means of support for their families. (However, married men could not avoid the draft.) Some of the draftees at the training camps were sent home because their behavior was incompatible with military service.

America's longstanding policy of neutrality was all but forgotten once war was declared. Citizens across the country began to display their patriotic fervor. Fund raising events were held to supply money for war bonds. In Charlotte, Queens College students provided entertainment for the soldiers at Camp Greene. Patriotic posters could be find throughout the streets and advertisements in support of the war ran in local newspapers and magazines. The country's patriotic devotion even affected American music. One of the most popular songs of the day was "Over There" by George M. Cohan. It captures the spirit of America's commitment to the Allies to help win the war.

Most American soldiers had idealistic views of war. Many of the draftees had never been as far as their hometown let alone seen the destruction caused by war. The total lack of modern communication, such as television, deprived the average citizen to see the massive destruction existed in Europe. Many images in local newspapers and magazines were cartoons or drawings and not photographs of death and war. This did not help soldiers who were illiterate. Soldiers who left with grand visions of war sometimes came back with changed attitudes. This would later influence the reluctance of many Americans to enter the Second World War.

Women and the War

Women were often at the train station to meet soldiers passing through town. Home-baked goods, friendly smiles and hospitality made the soldiers know that Charlotte was a patriotic town! They also put their efforts to more specific service.

Women were encouraged to meet at the Young Women's Christian Association (YWCA) on May 28, 1917, to formulate a plan where women would be trained to work in the factories and stores in place of the men who were drafted. A committee was established to assess the business needs in Charlotte and determine where the women would be needed and how to train women for these positions. For many women, it was the first time they had worked outside the home.

The naval department in Washington, D. C., made a policy that women would be paid the same wage as men holding similar positions. Departments were graded, as they are today, so that pay applies to each position, regardless of sex. Even though women did not participate in combat during World War I, they did serve the war effort in government positions, the Red Cross, the YWCA. and in medical occupations.

The YWCA and the local Red Cross chapter encouraged women to take first aid classes at the YWCA. If you were a member of either organization, you could take the course for 50 cents. First aid books were 35 cents. The first aid class for the colored branch of the YWCA. was held at the Good Samaritan Hospital under Drs. A. A. Wyche and E. F. Tyson.

Some private citizens became involved in entertaining the troops. Local Charlottean, Margaret L. Garrison ran a boarding house at 506 South Tryon Street. She invited several hundred people including her sixty-five boarders to attend a lawn party at her home in honor of Company B, Charlotte Engineers, who were leaving Charlotte. Garrison provided an elegant meal for her guests. Mayor Frank McNinch addressed the soldiers. The pastors of Trinity Methodist Church and Second Presbyterian Church provided devotional services. The Piedmont Orchestra members and some members/boarders who were living at Mrs. Garrison's home provided live entertainment. The next day, this group of 144 enlisted men and three officers left Charlotte for Goldsboro for more intensive training.

Mrs. Spurrier, a young widow living in western Mecklenburg County, allowed Camp Greene soldiers to visit her home and family. She lived near their rifle range and felt sorry for them having to walk so far, particularly on cold nights. She shared her food; home and warm fire many nights. The friendships that were made lasted beyond the war. The soldiers wrote letters to the family after they left Camp Greene. To see some of the photos made of these men and her family, please go to the Image Gallery and select "Photographs."

A hostess house was built at Camp Greene, where mothers, wives and girlfriends could visit. During the course of the war, it burned and was rebuilt. There were also churches and other places where the young soldiers and people of the town could spend time and socialize.

Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA)

The YMCA served a very important role in this war. It felt its purpose was to follow the flag around the world. It built huts in military camps in the United States as well as overseas to serve the men in uniform abroad. When the war was over, the organization remained in Europe for a while to continue their work while soldiers waited to go home.

The "Y" served the men in Charlotte as well as those at Camp Greene. It provided motion pictures, books, magazines and other types of entertainment for the soldiers. Writing letters home was an important activity for soldiers and was encouraged by the YMCA. Stationery imprinted with the "Y" logo was available in the writing rooms of the "Y" huts for soldiers to use. The "Y" logo can still be found on the surviving letters owned by family members and archival depositories.

A committee of eighteen local men was formed to address the needs of the YMCA. The committee anticipated that the men arriving in town would be interested in food, drink, recreation and the companionship of women. It was up to this committee to make sure that the men had these four needs met appropriately. Those who served on this committee were J. B. Ivey, W. S. Alexander, D. H. Anderson, W. B. Sullivan, M. B. Speir, J. A. Durham, C. O. Kuester, A. G. Brenizer, W. F. Dowd, Paul C. Whitlock, E. N. Farris, Rogers Davis, David Ovens, E. O Anderson, Rev. A. A. McGeachy, D. D., W. H. Belk, David L. Probert and George C. Huntington.

Camp Greene

The military selected the site for Camp Greene because of its access to transportation systems, a large source of water, and the amount of land available. The camp was built in record time, less than 90 days. By the end of the war, it had become a city unto itself. It had its own stables, bakery, laundry, hospital, chapel, YMCA buildings, Knights of Columbus hall, water tower and post office [5].

During part of the war, The Charlotte Observer, through the auspices of the YMCA, devoted a portion of its Monday newspaper to camp news called Trench and Camp. It was free to the soldiers and distributed from the YMCA at Camp Greene. This newspaper often included soldiers' names and personal humor that would mean little to the citizens of Charlotte. The Caduceus was the camp newspaper for the medical personnel.

The majority of the men who trained at Camp Greene were from Massachusetts. The military decided that northern soldiers would come south to train due to better weather conditions. The soldiers from Mecklenburg County were sent further south, mostly to Camp Sevier or Camp Jackson in South Carolina. The military's anticipation of good weather was dashed during the winter of 1917, which was cold, rainy and muddy. Men, animals and machines got stuck in the mud. Roads could not be paved or widened fast enough for the needs of the military.

The camp was segregated. Although mostly occupied by white soldiers, over 2,000 African-Americans arrived by train at Camp Green between July 29 and August 1, 1918. Holidays were often lonesome times for the soldiers, many of whom had never been away from home. The Camp prepared special foods and menus for these occasions. To see some of the images of the Thanksgiving Dinner menus, please go to the Image Gallery and click on "Images." To learn more about Camp Greene, please consult The Echo of the Bugle Call. (Miriam Grace Mitchell and Edward Spaulding Perzel, Dowd House Preservation Committee, 1979)

The Flu Pandemic of 1918

The Spanish influenza or "flu" epidemic of 1918 caused the deaths of 20 million people throughout the world. In the United States alone, 548,000 men, women, and children died during the epidemic. Where it originated or how is still debated. As the war drew to a close, many soldiers returned home and unwittingly brought the pestilence with them. The disease spread like wildfire. City officials did their best to ease the worries of their citizens, but the Spanish influenza was merciless. Entire families were completely decimated by the flu, which evolved into pneumonia, which killed weakened patient. Doctors throughout the country worked twenty-four hours a day trying to save their patients in the days before penicillin and other antibiotics were available. The first case in Mecklenburg County was reported on September 28, 1918 and the city was quarantined for two weeks beginning on October 4th. Ten days later 171 new cases were recorded that day. A week earlier, there had been 230 cases reported by 3 p. m. in one day! Volunteers from the community, particularly women who had already recovered from the flu, were asked to help. Extra beds were set up in hospitals.

Camp Greene was also quarantined for two weeks to try to prevent the spread of the illness. The city schools, church services and public meetings were all cancelled. The war was drawing to an end, but the flu epidemic hastened the closing of Camp Greene. Many soldiers died of the flu in the camp. Those who were able were shipped overseas and except for some African-American soldiers, the camp was empty.

The Changing Times

Below is a list of some of the transformations that occurred in Charlotte and Mecklenburg County due to the presence of Camp Greene and the demands on the home front during World War I.

- Citizens of Charlotte benefited from all downtown restaurants being cleaned up. One of the commanders at Camp Greene refused to let his soldiers eat in Charlotte due to the deplorable conditions. Restaurant owners made some improvements so that soldiers and citizens alike enjoyed a healthier eating environment.

- Local drug stores began using corn sugar for "before-the-war" grades of sugar. This new article, called corn syrup, was added to soda waters. The druggist used this substitution after using up their rationed sugar allotments.

- Citizens were asked to plant gardens [6] to help provide some of their own food.

- Reading on war subjects increased in the public library. A touring exhibit of three-inch shrapnel, four and five-inch shells as well as a Navy Lee rifle cartridge and other projectiles on tour were placed in the Carnegie Library in Charlotte where large numbers of people could view them.

- The Charlotte Chamber of Commerce sent a movie entitled Relatives and Sweethearts to Mecklenburg County soldiers in the 30th Division and other units in France to let them know how much they were missed and appreciated.

- The government censored letters from the soldiers and sailors. Friends and relatives back home received letters and postcards with words and sentences marked out. Cards and letters that could not be censored appropriately were thrown away and never reached the person.

- A patriotic concert was held at Lakewood Park, north of Camp Greene in April 1917. The Charlotte Municipal Band played the National Anthem, while the Boy Scouts from Troop 6 acted as a color guard. Lakewood Park no longer exists, but it was once a great source of recreation for the people of Mecklenburg County and the soldiers at Camp Greene.

- Liberty Bonds were sold to help pay for the war. A liberty loan worker heard this story about a 14-year-old boy named Emsley Austin. His brother, John Austin, was a gunner in the navy. He died in a naval hospital in Brooklyn in October 1918. The hospital personnel found $50 in his personal effects. His parents, Rev. and Mrs. D. M. Austin of Kingston Avenue decided to give the $50 to young Emsley. Upon receiving the gift, he promptly bought a Liberty bond as a memorial to his brother.

- On January 21, Charlotteans joined their fellow citizens in other states by participating in the first of ten "Heatless Mondays," ordered by the National Fuel Administration to conserve fuel for the war effort.

- Not all soldiers were on their best behavior. The amount of crime rose in Charlotte and Mecklenburg County with many soldiers breaking military rules or those of the city and county.

- Charlotte was considered a small town in the 1910 census with a population of 34,014. Mecklenburg County had a population of 67,031. By 1920, Charlotte's population had grown to 46,338, and Mecklenburg County had a total population of 80,695.