You are here

Chapter 1

THE ENTRY OF THE UNITED STATES into World War I was met with enthusiastic support from Charlotteans. They cooperated in every way from complying to "Heatless Mondays" to sending 1800 of their own men to fight. But of most importance World War I provided an opportunity to locate an army training camp in Charlotte. Charlotteans remember Camp Greene as "the best thing that ever happened to the city" Named in honor of the Revolutionary War hero, Nathanael Greene, the camp brought thousands of men from across the country and provided an economic boost to the city.

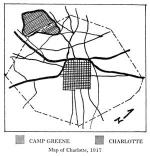

The coming of the camp turned the city upside down. Camp Greene unified the townspeople in one major effort -- to make camp life a mutual pleasure for both soldiers and civilians. The camp spurred Charlotte's growth as a thriving business center, helped double its population in the next decade and marked its entrance into the major league of New South cities. As a contribution to the war effort Camp Greene was praiseworthy, but as a contribution to Charlotte's overall expansion the camp was invaluable. For those who remember the Queen City before Camp Greene and witnessed the changes after, it is evident that its existence was the single most important factor in Charlotte's development this century. Located two and one half miles southwest of the city limits, Camp Greene became a reality in July 1917. From September 3,1917 to June 30,1919 there were from 30,000 to 60,000 men stationed at the camp -- making it virtually a "city within a city."

Since the early 1900s the Charlotte Chamber of Commerce had initiated various campaigns labeled "Watch Charlotte Grow." Following a slight decline in business and a rise in unemployment, projects to enhance Charlotte's industrial development were intensified. The government's search for a site to build a major army base offered the Chamber of Commerce an opportunity to revitalize their growth campaign.

Charlotte was competing with Syracuse, New York, Athens, Georgia and two other North Carolina towns -- Wilmington and Fayetteville. The preference for a southern location ruled out Syracuse as a real possibility. General Leonard Wood, commander of the Department of the Southeast, was to make a recommendation after an extensive examination of the sites. Only one camp would be built. Charlotte had three possible locations as potential campsites: one in the Myers Park development, one in the northern section of the city and one in the southwestern section. Charlotte hoped to be chosen for the site as such a facility promised to bring numerous people, jobs and industry to the area.

The Chamber of Commerce made elaborate plans for the visit of General Wood. Charlotteans were encouraged to attend all the festivities and hang flags to display their patriotic enthusiasm. The excitement concerning the visit was everywhere. The newspaper recounted the feats of Wood's outstanding military record including his role as the commander of the "Rough Riders" during the Spanish-American War and his service as military governor of Cuba. He had gained the respect of his superiors and the admiration of all Americans. In Europe, he was regarded as a soldier of high capabilities and his achievements were described in glowing terms:

You did not need to look at the crown and stars on his sleeves to know that he was of Colonel's rank. His very presence radiated authority and commanded respect. There was a firm handshake and the quiet, cordial greeting of the British soldier.

Wood's busy schedule caused several delays in his plans to visit Charlotte. Word arrived that he was definitely coming on July 5, 1917. As his special train crawled toward Charlotte, Wood confided that he was approaching the city with an open mind. Because of pressing business at department headquarters in Charleston, he would only spend one day inspecting sites. Although the day was for that one purpose, Charlotteans planned to make the most of it and arranged "red carpet" treatment. Accompanied by his personal staff, General Wood arrived at 11:00 a.m., July 5, 1917 from Athens, Georgia. Met at the Southern Railway passenger station by a small reception committee headed by Z. V. Taylor, he was driven to Taylor's Myers Park home (later purchased by James B. Duke) for a brief rest. In his blunt manner, General Wood announced: "I have come to see the sites offered the government for training camps and the festivities which may be connected with my visit will have to take second place." When asked how long he thought it would take to investigate them, he said, "As long as is necessary to get in all the facts in this case. This is purely a matter of business with me and it is my business to see the sites offered, to go into the advantages offered by the city and to gather all possible information which will bear upon the matter of the location of the camp."

One site was inspected in the morning and the other two in the afternoon. General Wood, interested in the soil at all three sites, stated that the nature of the soil was well-suited to the use of the camp. He had been under the impression that the soil was red clay and found that while it was red, it was more of a sandy loam -- far preferable. All three sites had been offered to the government free of cost.

The investigations were interrupted by a luncheon at the prestigious Southern Manufacturers Club. The Chamber of Commerce had the best cooks and wine available for the affair. Many said that it was this lunchtime "wining and dining" that enamored General Wood to Charlotte. After several glasses of wine he freely admitted that he was impressed with Charlotte, but warned that his aides were investigating other areas and must be consulted before any decisions were reached.

The afternoon investigations were followed by the only public meeting of the visit. This was the single chance most Charlotteans had to see and hear their distinguished guest. At 6:00 p.m. General Wood spoke to about 8,000 spectators who "stood at attention" on the lawn of First Presbyterian Church while he told of the unpreparedness of the country and how the condition ought to be remedied. ( See Appendix B.) Few people left the grounds during the speech though it was supper hour for most. The great crowd's prolonged applause demonstrated their delight with Wood's remarks.* (* Shortly after his Charlotte visit General Wood's criticism of President Wilson's policies contained in his speech and several informal statements appeared in an article in the Saturday Evening Post. His statements about the impracticality of Wilson's scholastic approach to the handling of military affairs were factors leading to his being overlooked for the position of Commander of the American forces. Within days after the publication of his comments, General John Pershing was named.)

Unaware of the possible consequence of the candor of his remarks, the General continued with the remaining events of the day including a formal banquet held at the Selwyn Hotel. The hotel was decorated with flags and red, white and blue streamers. The only speaker was General Wood with Z. V. Taylor presiding. The Chamber of Commerce had even invited Theodore Roosevelt who sent his regrets in a letter read by Mr. Taylor.

My Dear Mr. Taylor:

I wish it were possible for me to come but it is absolutely out of the question. I can hardly say how greatly I admire my old friend and comrade, General Wood, and how heartily I believe in him, both as a soldier and a citizen.

Faithfully yours, Theodore Roosevelt.

Z. V. Taylor introduced General Wood and presented him with a leatherbound copy of a souvenir book published by the Charlotte Observer containing photographs and sketches from his career. His speech stressed the need for national unity and aroused an appreciation for the crisis that confronted the nation. Several of the problems in selecting the site were discussed and some of the advantages of a North Carolina camp were reviewed. ( See Appendix C.) At the conclusion of the address, Mr. Taylor dismissed the crowd requesting that all the National Guard in attendance remain and be presented to the General. Impressed with all the honors, the General was driven to the Southern Railway station where he departed at 11:00 p.m. for Charleston.

Wood had been careful not to commit himself officially. He emphasized that Charlotteans must realize that it was too soon to make any announcement. Each city and site would be analyzed on a "credit and debit" system to determine relative values. The three cities in his division showing the highest average would receive his recommendation for the location of a camp. He left saying that he was truly appreciative for the hospitality he had been shown and that he would be as fair as possible in his decision.

While in Charlotte, Wood had expressed a preference for one of the three local sites inspected. Soil conditions were the primary reason for the selection of the site located between Sloan's Ferry Road and Tuckaseegee Road. The tracks of the Southern Railway system paralleled Sloan's Ferry Road while the lines of the Piedmont and Northern paralleled the Tuckaseegee Road offering good transportation advantages by rail as well as macadam roads. The location also included two high elevations as possible headquarters sites overlooking the entire proposed camp area -- the old James Dowd house on Sloan's Ferry Road and the Sid Alexander place on Tuckaseegee Road near Lakewood Park.

The topography of the land was also ideal for the building of the tent city. The land was rolling and many small streams would make drainage easier. There was an abundance of wood, some heavy timber, arid many large fields. Wood noted other advantages such as the number of crossroads that could be placed in shape quickly, the number of existing crossroads, and the excellent water supply. And lastly, he noted the public spirit in Charlotte was "fine."

Encouraged by General Wood's comments and hoping for approval, the people of the city started preparing the campsite so that construction could begin immediately. Farmers cleared acres of woodlands and blooming fruit orchards. Crowds of people flocked to what was to be camp headquarters (the Dowd house) to get a job. The rumor was that the army was going to pay five dollars a day for work, no matter what the job. At the time, one dollar a day was considered good pay and the increase made the camp a veritable gold mine. People came from miles around bringing their own tools. Everyone from shoe clerks to railway employees quit their jobs to work building the camp. The "boss" stood outside the temporary headquarters and asked for draftsmen, engineers, construction workers and a variety of other skills immediately needed. The government men simply selected men at random from the raised hands and shouts of the crowd. They were told to be at the Selwyn Hotel the next morning to see Mr. W. C. Cummins, the representative from the Consolidated Engineering Company of Baltimore. Mr. Cummins had been sent to line up jobs to get the camp built if confirmation was received. The lines to see him extended more than a block. Men were hired with little concern for written credentials or experience. They were instructed to work as rapidly as possible to produce the blueprints.

While optimism and enthusiasm pervaded the local front, a hot fight was being waged in Washington, D. C. among the delegates from Fayetteville, Wilmington and Charlotte. Charlotteans, already encouraged by General Wood's favorable remarks, were ecstatic when he dispatched two members of his staff -- an engineer and a medical officer -- to inspect the site. News began to spread that Charlotte was practically assured of the camp. When Charlotteans learned that a Fayetteville delegation was in Charleston lobbying with General Wood, they mobilized their own delegation to plead Charlotte's case in Washington before the decision was made.

The Charlotte delegation, headed by Z. V. Taylor, Cameron Morrison, Mayor Frank McNinch, David Ovens and including 32 others, waged "one of the hardest fights staged in Washington between North Carolina delegates that had been recorded in a long time." Mayor McNinch reported on July 10, 1917 that Charlotte had not yet been designated and that Wilmington and Fayetteville were lobbying hard. Secretary of War Newton D. Baker was to meet Charlotte's representatives the next day.

Within a few days after the delegates' return, reports began to pour into Charlotte from various sources saying that General Wood had selected Charlotte -- his reasons being the inadequacy of the water supply at Fayetteville and the excellent conditions in Charlotte. Even the Fayetteville delegation wired their congratulations to the Charlotte Chamber of Commerce. In the same telegram they sought Charlotte's support to obtain a camp for Fayetteville. The Chamber was surprised but cautious and replied that they would be happy to help when they were officially notified that Charlotte had indeed been chosen.

Confirmation became more important than ever and the committee decided to send another delegation of eleven to Washington headed by Taylor, McNinch, Morrison and Ovens. Unofficial announcements were still being received and the news spread that Charlotte had been definitely selected as the campsite. The War Department had still not issued a statement. The morning after the delegation arrived, Joe Garibaldi of the Chamber of Commerce received a telegram from Chairman Taylor saying that a hard fight was sure to be staged before anything would be done by the War Department. Garibaldi was asked to gather a large delegation and come to Washington. As the enthusiastic group boarded the train, one member was heard to say, "If Charlotte does lose, the delegates will have turned Washington upside down in the fight."

Secretary of War Baker was ready to make an announcement on July 12, 1917 but he was suddenly confronted with three delegations from Charlotte, Fayetteville and Wilmington, each insistent upon being heard. Politeness and curiosity compelled him to listen. The Charlotte delegation arrived at 10:00 a.m. Secretary Baker told them that he had received General Wood's recommendation in favor of the Queen City and his intimation that "General Wood's choice was the choice of the War Department" was so clear that the delegates cheered. This was followed by congratulatory handshakes but still no official confirmation.

When the Fayetteville delegates arrived Secretary Baker read General Wood's letter in favor of Charlotte and the reasons. The delegation charged that the two North Carolina senators, Simmons and Overman, had unfairly lobbied for a Charlotte location. Charlotte delegates indicated the two senators had worked only to obtain a camp for the state and not for a particular site. Simmons and Overman denied any favoritism providing the same hospitality and support for all possible locations. Charlotte took the stand that the choice was based only on General Wood's decision -- Fayetteville was certain politics was the major factor. Wilmington delegates decided not to fight the choice and instead argued for a second camp in North Carolina. Meanwhile matters were complicated by a rumor circulating that the original plans for the camp had to be enlarged and that the Charlotte site was unsuitable.

The waiting ended a few minutes after 5:00 p.m. July 13, 1917. The Charlotte delegation telegrammed the Charlotte Observer saying "Charlotte gets camp." Eight minutes later, another telegram arrived: "Secretary of War Baker at 4:30 p.m. officially and finally located military camp at Charlotte."

The news brought excitement and relief to Charlotte. The advantages of being chosen were obvious, but now people began to consider the negative factors. A natural fear developed that a military cantonment would affect moral values. Would it be "riff-raff" coming to Charlotte or the finest class of young men in the country -- the same class which responded to the call for selective draft in Charlotte? Could they expect the same from the New England troops who would be coming? These young men would surely come from homes of refinement. Charlotteans convinced themselves that it would be gentlemen who predominated the National Guard training camps.

Any fears were laid to rest when it was learned that the War Department insisted upon requirements for every camp. One, the city government must have the liquor traffic under strict and effective control; and two, moral conditions must also be under control and be maintained at a satisfactory level. No camp would be allowed to continue where these standards were not maintained. Camps in other parts of the country had been removed for these reasons and Charlotteans were comfortable with the knowledge that low standards would not be tolerated.

Another area of concern was the problem of health and sanitation. Mayor NcNinch spent two days in the United States Health Department in Washington and with national police officials securing valuable information to help him meet conditions which the camp would impose on the city government. The United States Health Department sent two officials to assist in the proper sanitation of the city and camp. From the police, information was obtained to enable him to organize and maintain a system of security. This included an increase in the police force and extension of control, particularly over the sale of whiskey. The government exercised strict control of the troops relieving most of this extra responsibility from the local police. Despite all these preparations some citizens still had misgivings.

Many people in Charlotte believed that the camp was altogether independent of the war and that it would remain in operation long after peace was declared. They believed that it would be in existence for six to eight years or longer. With that in mind, people were concerned with the camp's long-range influence on the community. They were skeptical as to whether or not the new regulations and controls could be maintained over an extended period of time. It was clear that a demand for vast stores of food would bring unprecedented pressure on the local markets. With the troops and consequent flood of visitors, Charlotte would find itself with a transient population of at least 100,000 people in just a few weeks. Additional housing outside the camp would be necessary. While much of the work would be done by Charlotte contractors, the actual construction necessitated a work force larger than the local area could supply. It was feared that the regular labor force would be lured away by the higher wages of camp construction. The construction of the camp would be under the direction of I. W. Littell of the Quartermaster Corps. The government was required to abide by a regulation that wages paid under government contract were to be based on the wages prevailing in the community on the first day of June 1917. Hopes were expressed that the regulation would be strictly enforced as the construction went into full swing. Despite all these potential problems, Charlotteans were still for the camp.

Less than a week after the official confirmation, the possibility arose that Charlotte would lose the camp altogether. When Charlotte was first designated as a location, about 2500 acres were offered to the War Department and had been accepted as a suitable amount. When the actual laying out of the area began, however, Lieutenant Colonel Ladue, the chief engineer from General Wood's staff, found that part of the original site was not suitable. In the meantime, the number of men expected to train here had grown from about 30,000 to almost 50,000 so that more land was needed in addition to replacing the unsuitable portions of the original 2500 acres. Also necessary were adequate places for artillery and rifle ranges and open space where maneuvers could be conducted. Major Kilbourne, General Wood's chief of staff, arrived in Charlotte on July 23, 1917 for a final inspection. A local committee was with him all day and appropriate space was found for target ranges.

Lieutenant Colonel Ladue arrived on July 24, 1917. He had been assigned the task of deciding whether or not Charlotte would get to keep the camp. The biggest problem was obtaining the additional land for conducting maneuvers. The cooperation of the townspeople was crucial. The government was ready and willing to pay reasonable amounts for private land, but made it clear that it would not pay an exorbitant price. There were too many places the camp could be moved instead of dealing with those wanting to get rich at the government's expense. The government's position was clear -- Charlotte must furnish enough land for the training of approximately 50,000 men by midnight July 24 or the camp would be moved. The committee had done a superb job of planning for what they thought would be 20,000 soldiers. With the news that the number would be more than doubled ( in addition to 12,000 horses) they quickly had to make major adjustments. The committee persuaded General Wood to postpone the decision for one more day pleading that had they known earlier, they could have had the necessary land by midnight.

An emergency meeting of the Chamber of Commerce was called and all citizens were urged to attend. Mayor McNinch and other members told of the requirement for more acreage. They let it be known that unless adequate land for the rifle range, a base hospital, grounds for maneuvers, and an aviation field were supplied the camp would be moved. Cards were passed urging those present to contribute as much as possible. A considerable amount of the $75,000 needed was raised at the meeting and several committees started canvassing the city.

As if things were not bad enough, Charlotte was plagued by a competing offer made to the government by Savannah, Georgia of a campsite of unlimited proportions. In addition, Savannah's deal included a twenty-inch water main; a 250,000 gallon reservoir built anywhere on the campsite the government designated; unlimited and free use of storage warehouses in the city; and the construction of three roads through the camp. Charlotte's offer paled into insignificance beside that of Savannah. Another factor seemed to add to the appeal of Savannah as a site. Most of the soldiers coming to Camp Greene would be from the Northeast. Therefore a majority of them would be Catholic. Savannah had numerous Catholic churches and predominantly Protestant Charlotte had few. It was rumored that Colonel Ladue (and most of his aides) being Catholic would favor Savannah for this as well as the other reasons. Given the responsibility for making the final decision, the townspeople were sure Ladue would choose to do away with the Charlotte camp.

In the meantime, New England army officers from the Quartermaster Department were already flocking to Charlotte and the streets of the city were taking on a military air. In hotel lobbies, khaki was conspicuous. The New Englanders were pleased with Charlotte and openly supported the original plans to build the camp here. Some had already planned to bring their families and were looking for homes.

With unbelievable efficiency, the Chamber of Commerce managed to raise the money and land necessary. Lieutenant Colonel Ladue and Major Kilbourne divided the job of inspecting the grounds one more time and met at the Southern Manufacturers Club with members of the committee. The next day, Colonel Ladue wandered over the camp and stood nervously in front of the headquarters. Carefully considering the options and tapping his riding crop against his leg, he pondered the situation. The committee watched Ladue's every move with anxious anticipation. Impressed with the great amount of work already done, he turned slowly to the crowd and announced, "The camp will stay." Everyone cheered as the last obstacle to the establishment of Camp Greene was removed.

The work on the camp went ahead with redoubled energy. General Wood visited the city on August 6, 1917 to examine the progress of the camp. Much of the area he had seen on his last visit had been virgin forest and growing crops. A considerable change had taken place with acres of trees chopped and narrow roads cut. The entire area was a beehive of activity. Later in the evening, General Wood was once again entertained at the Southern Manufacturers Club by members of the Chamber of Commerce arid other prominent Charlotteans. After dinner, he made several suggestions to the local citizens concerning ways to make the soldiers' stay more pleasant. First he encouraged the people of Charlotte to make the soldiers feel at home. Retailers should keep prices down and the amusements near the camp should be controlled. Transportation between the camp and the city should be facilitated, and accommodations for visitors and wives provided. Finally, he recommended a board of arbitration to appraise and settle any damages that might be caused by the maneuvers of the troops. He told of an incident outside of Boston where artillery firing had caused plaster in a house to fall. On entering the structure he saw the occupants to be a drunken man and a small boy. The parent was too far gone to pay any attention so the general addressed the boy:

"Much harm done, boy?"

"Taint nothin' to what'll happen when Ma gets home," replied the urchin.

The suggestions proved helpful and were followed as a guideline for dealing with the various aspects of camp life. With the fight won and the initial preparations made, the serious business of building Camp Greene began. Charlotteans had worked hard to have their city chosen as a site for the training camp. The Chamber of Commerce led by Mayor Frank McNinch, David Ovens, Cameron Morrison and Z. V. Taylor turned Washington upside down to convince the powers that Charlotte was the correct choice. When threatened with loss of the camp due to last minute demands by the government, Charlotteans met the challenge with wide community support removing the obstacles. Camp Greene was to be a reality -- Charlotteans had reason to be proud of the community spirit which brought the reality to fruition.

Mitchell, Miriam Grace and Perzel, Edward Spaulding. The Echo of the Bugle Call: Charlotte's Role in World War I. Charlotte, NC: Dowd House Preservation Committee, 1979.