You are here

Chapter 2

IT TOOK NATURE AND MAN 150 years to build Charlotte into a city of 50,000 people. The government built a city of equivalent size in west Charlotte in less than 90 days. The campsite was 2,340 acres of farm country with a total population of perhaps 75 and cotton growing waist high. The rapid transformation of this rural countryside into an active military center was phenomenal.

On July 16, 1917 Major Clarence H. Greene of the Rhode Island National Guard arrived to assume command of construction of the camp. As construction quartermaster, he was the personal representative of the United States government. He immediately inspected the campsite, secured blueprints and maps, and plotted the camp's general layout. Three days after his arrival the War Department awarded the contract for building the camp to the Consolidated Engineering Company of Baltimore, Maryland. Although a relatively new corporation established in 1911, Consolidated Engineering was chosen for one good reason -- its reputation for fast construction. Baltimore's filtration plant (one of the largest in the country) was constructed by the company 263 days ahead of schedule. In Memphis, Tennessee, construction of a skyscraper was begun on May 1; on October 1 of the same year, the building was occupied. The company had been honorably mentioned in the Southern Railway magazine for its rehabilitation in record time of the Asheville-Salisbury line after the flood of 1916.

W. C. Cummins, the general manager of the engineering company, had been in Charlotte organizing the project and hiring men. On July 23, 1917, actual construction began. Cummins put a work force of 1200 men in the fields and continued to hire until 7,856 men were busy carving Camp Greene out of the rural Mecklenburg countryside. Cummins' assistant, A. H. Hartman, had the major responsibility of purchasing construction materials. The secretary of Consolidated Engineering, Clarence E. Elderkin, arrived in Charlotte to handle finances arid auditing. Altogether he handled a payroll of over $1,500,000. On each Saturday afternoon, more than $100,000 was paid to the construction workers by his office. The general superintendent, John H. Stolfort, was in charge of building materials. Under him were a number of superintendents, each with the responsibility of building specific units.

A complex system was carefully and faithfully followed. Laborers, carpenters, mechanics and other workers were divided into units under the supervision of foremen. The foremen reported to superintendents who in turn reported to an assistant general of supply and so it continued up the ladder of a highly developed pyramidal managerial structure. Each man was assigned a particular duty. No department head passed over the head of an official immediately above or below him to issue orders or information. Each order passed systematically from the general manager to the mechanic or laborer at the bottom. The specific instruction issued to each man was to mind his own business -- failure to do so resulted in immediate dismissal. The end result of this system was order and efficient production.

According to one eyewitness, Harry Dalton (who became an important business and civic leader), confusion existed over which workers were soldiers and which civilians. Each had his own set of regulations and superiors. Army men were required to wear the proper military attire which made them easier to distinguish. The "skull caps" so popular with the civilians were not to be worn by the soldiers. On one occasion, a commanding officer spotted a man who appeared to be a soldier wearing a "skull cap." He ordered the man immediately to his office and proceeded to lecture him harshly and at great length about the appropriate dress for a soldier at work. The young man tried to protest and explain that he was a civilian. Finally, when the irate officer paused to take a breath, the innocent citizen managed to make himself heard. The embarrassed officer reddened and apologetically dismissed him. Such episodes were not uncommon.

Fire prevention, medical attention, sanitation, an adequate water supply, feeding and housing the men, policing the grounds, enough wood, and finally and most significantly, the weather were everyday concerns facing Consolidated Engineering's management. The fire protection plan consisted of a well-organized fire department on the campsite at all times with a horse-drawn chemical engine. Fire guards, prepared for quick response to alarms, were stationed about the camp at night. The sick and injured were taken care of by a central "hospital" operated by two resident civilian physicians and their aides. Motor ambulances stationed at locations throughout the camp were readily available to respond to accidents. Sanitation around the camp was the duty of five 25-men squads. The crews covered all stagnant pools with oil, built and fumigated latrines, closed polluted streams and daily picked up bottles and scraps from the grounds. It was reported that "not a mosquito had been seen in the area and not one man reported to the 'hospital' for sickness" during the initial phase of construction at the camp.

The water supply of the camp was obtained from artesian wells dug at points about the camp. The supply was supplemented by motor-driven wagons carrying water from Charlotte to permanent tanks located throughout the camp. Workmen were supplied with water from the tanks by water boys carrying buckets and ladles. Food and housing were handled by the commissary manager. Mess tents and sleeping tents were used for quartering the men. Each worker was provided with a cot, sheets, a pillow, and blankets. A porter was placed in charge of every 25 beds to be sure that the sleeping quarters were kept clean and in order.

The actual policing of the camp was done by units of the National Guard, special watchmen, and four secret service men who worked undercover as laborers or carpenters. The chief of the secret police had worked on major construction contracts, including the Panama Canal, but had "never met a cleaner body of trained and efficient men than those with whom he came in contact at Camp Greene." With a company on the job as efficient as the Consolidated Engineering Company of Baltimore, it is no wonder that reports of "constructing a building an hour" were heard once the work was in full swing.

The weather and lack of building materials were the greatest obstacles in the construction of Camp Greene. The first contract called for the erection of 940 buildings for which there was ample lumber. However, changing plans resulted in a camp of close to 2,000 buildings. It had been estimated that the camp would be ready for the first division by August 25 provided the appropriate quantities for all needs were met and more wood came. With the increasing demand, lumber shortages became common. For example, on August 2, 1917, 20 cars of lumber due earlier were reported lost! Not only did shortages impede the building, but they caused a layoff of 200 carpenters. Despite the annoying delays, the engineers were determined to keep on schedule and many of the structures were built with green lumber.

The weather remained a disrupting factor during every stage of construction. In the early periods, endless rain turned work areas into seas of red mud. Construction activity in the winter months was hampered by unprecedented low temperatures, ice and snow. Thawing created mud and slush and worsened working conditions. Weather became such an influencing factor that four soldiers were assigned the task of becoming active meteorologists so that construction plans could be coordinated with weather conditions. These men were detached to the Charlotte office of the United States Weather Bureau for a period of seven weeks for meteorological instruction. Weather became the first consideration prior to starting any new project.

The temporary headquarters for Camp Greene was the James C. Dowd house. Its location overlooking the camp area made it an ideal center for construction activity. Built in 1879, the quaint old house had a large master bedroom with a huge fireplace. This room was converted into the main office for the workers during the cold winter. Although meant to be a temporary headquarters, the Dowd house became a center of activity throughout the stay of the army in Charlotte. An addition was made to accommodate such necessary offices as accounting and payroll. One of the secretaries who worked in the house during the construction phase was Mrs. William Rigsby of Charlotte. Mrs. Rigsby's grandfather had owned the house, and the office she worked in had been her Aunt Blanche's bedroom. In 1918, the camp headquarters moved out of the Dowd house but the house remained as the construction headquarters.

A special resolution of Congress provided a civil engineer experienced and trained in constructing public works to serve as supervising engineer. He assisted the quartermaster corps in the variety of engineering problems of design and construction that arose. Colonel J. L. Ludlowe of Winston-Salem was selected for his knowledge in such matters as water supply, streets and roads, sanitation arid drainage. During the active period of construction, Colonel Ludlowe was one of the busiest men in the entire organization. In addition to keeping close touch with all branches of construction, he was active in inspiring the "hurry-up" spirit evident throughout the working force making early completion possible.

When construction actually began, the very first things built were troughs for the animals. Nothing else was started until these long structures were completed. They were supervised with the same care and precision that all the buildings were given. Next followed the laying of water mains. By late July, Camp

[At this point in the original book, thirty two photographs were inserted. See this separate display of them for the online version]

Greene was a beehive of activity. Along the Dowd road, quarters for twelve companies of 150 soldiers each were already marked out. An army of carpenters was at work constructing the mess buildings. Isolated regiments under the direction of sunburned officers appeared over the area engaged in specific tasks. Major Greene was overseeing all phases of construction.

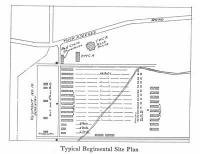

Each regimental area consisted of a headquarters, mess halls, shower and bath buildings and a tent area for sleeping. It took 35 acres to house and feed one regiment. Each company had a separate mess hall 130 feet long. Only when all this is multiplied by 190 regiments plus brigade and divisional headquarters, a hospital and other support services can one comprehend the immensity of the undertaking. The Army attacked the task in a machine-like manner, grinding out results never before witnessed in Charlotte. At the end of the first week of construction three mess halls had been completed and a dozen other buildings were well under way. Approximately 2500 men were on the payroll, receiving thousands of dollars weekly, most of which was spent to bolster the Charlotte economy. During this time more land in the area of Statesville Road had been obtained for the rapidly expanding camp.

Each day saw great changes at Camp Greene. From the porch of the Dowd house where work had first begun, at least twenty big sheds could be seen in the area around the Alexander house a mile away. One official estimated about ten miles of roads were in constant use during the construction phase of the camp. An extensive system of drainage ditches throughout the camp had been completed. Two lines of double streetcar tracks to Camp Greene were completed by the Southern Public Utilities Company. The main line ended at the northern boundary of Camp Greene. The other line was a spur off the Hoskins line at a point near Lakewood Park and ended at Tuckaseegee Road opposite the base hospital. Loops at the camp allowed the trolley to turn around for the return trip to the city. The increased traffic necessitated overhaul of the open or summer cars, addition of trailer cars and the purchase of new cars larger than those operating within the city.

On August 14, 1917, W. C. Cummins announced that Camp Greene would be ready within a week. This surprised Charlotteans who were under the impression that mid-September would be the earliest date. Many changes had been made in some of the previously planned buildings. For instance, the hospital was to be a base hospital instead of an ordinary field hospital. It covered sixty acres instead of the forty acres typical of most base hospitals. The cost of the plumbing, wiring, heating, and sewer system for the hospital was over $500,000 and the complex used more lumber than had been used in the original 964 buildings. The number of beds totaled more than 2000 - 500 more than placed in the average camp hospital. This would be only one of the 62 buildings located to the west of the Tuckaseegee Road. The remount station (stables) contained structures a total of 6000 feet in length - 720 feet more than a mile! There were hayracks, feeding racks and water troughs as long as the building. In addition there were loading and unloading platforms, sheds for wagons, pack mule stables and stables for horses. The health of the horses was also to be protected by a modern up-to-date veterinarian's facilities, a sick corral and a convalescent corral. The complete remount station covered over one hundred acres.

The President of the Consolidated Engineering Company of Baltimore stayed in constant contact with General Manager Cummins at Camp Greene. On August 24 he visited and commented on the rapid progress. "Except for the inability to get all the materials needed, I do not see that the work at Camp Greene could be in better condition." The contract had been awarded just thirty days before, and all the buildings specified in the original agreement were completed! Furthermore, buildings provided for under supplemental agreements were well under way. It was reported that more than 1000 buildings were finished with the exception of minor furnishings. On August 28, 1917, Camp Greene, as originally planned, was completed -- only one week later than Cummins had predicted. Construction was nearing completion on the base hospital, remount station, and the 300 brick incinerators needed to burn refuse. Most of the buildings completed in this initial phase were not sleeping quarters and the soldiers who arrived on September 3, 1917 had to sleep in tents.

Construction did not end in 1917 but continued at a steady pace through 1918 and 1919. As early as January 5, 1918, preparations were made to enlarge Camp Greene. Major A. B. Kaempfer, camp quartermaster, was in charge of construction at the time. The order to expand the camp contributed to the city's hope that Camp Greene would become permanent. The dispatch sent to Major Kaempfer ordered the construction of "barracks"; the Associated Press had declared "barracks" would be built. The word "barracks" connoted the possibility that the new structures at the camp would indeed be permanent. However, Charlotte's hopes in this matter would never be realized.

The expansion provided accommodations for 7,000 more men at an approximate cost of $200,000 -- an addition of another division to Camp Greene. More land had to be purchased directly from the owners and again the government made it clear it would not pay unrealistic prices. The additions were finished by March 1. The new barracks were only temporary structures and although some tented areas were replaced, the majority of men continued to be quartered in tents. Camp Greene was now able to accommodate eleven infantry regiments, three artillery regiments, one ammunition train, signal corps, headquarters corps, engineering corps and sanitary train. By the end of January 1918, quarters for six machine gun battalions had also been added.

The expansion of Camp Greene was strong evidence of the satisfaction of the War Department with the Charlotte location for the mobilization and the training of troops. Few other camps built during the same time had been enlarged. In March 1918, an additional $500,000 was expended to put the camp into "shipshape" condition including an up-to-date sewerage system and first-class roads. Despite the success of the Charlotte camp, North Carolina's United States Senators Overman and Simmons were unsuccessful in their attempt to have other camps built in North Carolina.

Several non-military buildings were constructed at the same time the camp was being built. Miss Fay Kellogg, representing the National Board of the Young Women's Christian Association, arrived from New York City in August 1917. She was in charge of designing and erecting a Hostess House or clearinghouse for all women relatives of the soldiers. It included a reading room, writing room, restroom, and hospitality room complete with an open fireplace. Great wicker chairs and couches with comfortable cushions, harmonious wall hangings and paintings added to an atmosphere of home. The house was designed to be a pleasant retreat for all seasons. In March of 1918 the Hostess House burned down. The facility was temporarily located in a mess hall near the Red Cross headquarters and later moved to the Harris house on the Tuckaseegee Road near the entrance of the camp. A new, large two-story Hostess House was built by September 1918.

Another recreational facility constructed was the Soldier's Club at 516 South Tryon Street. Most of the lumber for this structure was donated by three Charlotte firms: J. H. Wearn and Company, J. W. Lewis and Company, and the Doggett Lumber Company. An open air pavilion was used to stage concerts and dances. The Soldier's Club also had such "luxuries" as shower baths, equipment to serve lunches, plus many other extras. Most of the construction of these recreational facilities was done by the Motor Mechanics (Motor Macs) from the camp.

The need to create an instant city required the design and construction of a number of specialized facilities. An extensive telephone system was built with its own switchboard. The magnitude of the telephone system entailed a separate building for its exclusive use. A separate branch post office was constructed to handle the camp mail. With a payroll for an average of 4,000 construction workers, a new building was built to house twenty paymasters. The largest of the special services buildings was the bakery. Three bakery companies from Gettysburg, Pennsylvania were permanently stationed at Camp Greene. They provided bread for the entire camp -- prepared in dozens of ovens capable of producing 40,000 two-pound loaves at once.

Rifle and artillery ranges were built in the fall of 1917. Major Liggett chose a site near the Catawba River (about eleven miles from Charlotte) to construct a range for rifles, pistols and machine guns. An artillery range and small camp was situated on land acquired by W. T. Rankin at Kings Mountain near Gastonia. Roads were built connecting these facilities with the main highways to Camp Greene.

The total area of the main camp when all the building was completed was as follows:

Regimental Reservation 589 acres

Quartermaster houses, etc. 62 acres

Hospital 110 acres

Remount Station 139 acres

Detention Camp 35 acres

Remainder 1216 acres

Subtotal 2151 acres

Drill grounds outside camp 90 acres

Land adjoining Camp Greene on West 487 acres

Total 2728 acres

The cost of the camp was a matter the War Department was not particularly anxious to have published. It was estimated, however, that as of June 30, 1919, the cost was well over $4,797,000 for the entire reservation covering over 6,000 acres. It was a well-known fact that the wages paid at Camp Greene amounted to over $1,000,000. A total of 1629 carloads of materials had been received at Camp Greene in the first five months alone! Hundreds of thousands of bricks were used in the building, with over half a million alone going to build incinerators. A total of 23,000,000 feet of lumber (or 23,000 wagonloads ) was used in the actual construction. This is comparable to a boardwalk of lumber two feet wide stretching from Charlotte to the Golden Gate. The electrical contract for Camp Greene, held by Tucker Luxton, required the use of 301 miles of wire, 1500 lamps and ten carloads of poles. Over twenty-five miles of road, 3,000,000 feet of wire, and 50 miles of water pipe contributed to make Camp Greene virtually a city within a city.

The construction phase of Camp Greene was exciting. Buildings sprung up over night. Millions of dollars of materials and wages were pumped into the Charlotte economy in a short period of time. The constantly changing plans to enlarge the camp encouraged Charlotte that the United States government had permanently invested in its future. Time and the end of the Great War would change that perspective.